This week on Acta Non Verba I’m continuing my conversation with Donald Robertson as he dives deeper into Stoicism and shares simple strategies for applying its principles to your daily life. In this episode Donald and I also discuss how he has embraced Adversity, using the lessons of global and personal history to transform how he thinks about his career and his life.

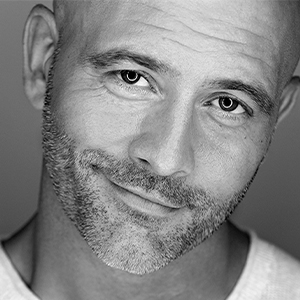

Donald Robertson is a cognitive-behavioral psychotherapist, trainer, and writer. He was born in Ayrshire, Scotland, and after living in England and working in London for many years, he emigrated to Canada where he now lives.

Robertson has been researching Stoicism and applying it in his work for twenty years. He is one of the founding members of the non-profit organization Modern Stoicism.

Donald is the author of How to Think Like a Roman Emperor.

Connect with Donald via his website: https://donaldrobertson.name/